Gender and Racialized Perceptions of Marriage Migration in Heterosexual Mixed-Race Marriage

Nissa Vidyanita

University College Dublin

Article. 2025, Vol. 3(2): 57-76.

https://doi.org/10.65621/BZJM6748

ABSTRACT

Colonial legacies have not only shaped social structures but have also contributed to the construction of the ‘ideal’ marriage partner. In the Indonesian context, the notion of ‘ideal’ partner aligns interconnectively with racialized ideologies. Thus, the social phenomenon of ‘mixed-race marriage’ in Indonesia is widely perceived as improving bloodline and economic gains, as legacies of colonization. This study examines how colonial histories and normative gender ideologies influence perceptions of mixed-race—particularly at the intersection of race, gender, colonial legacies, and media representation—significantly on Instagram. Utilizing critical discourse analysis, this study investigates media representations on Instagram accounts managed by women digital creators married to men of different racial and national backgrounds. This research explores how media representations shape public perceptions of gender, race, and colonial legacy in the context of mixed-race marriage. By analyzing curated content on Instagram, the study examines how digital platforms reflect and reinforce dominant ideologies rooted in colonial histories—particularly those that privilege whiteness and influence notions of desirability.

KEY WORDS

mixed-race marriage, colonial legacies, marriage migration, racialized ideologies

Introduction

In recent years, transnational and mixed-race marriages have become increasingly visible within Indonesian society, reflecting broader processes of globalization, migration, and shifting cultural values. These unions often generate intense public debate, as they are situated at the intersection of national identity, gendered expectations, and racialized imaginaries. A recent example is the social media campaign ‘To Be Indonesian Mixed-Race 2045,’ which sparked widespread attention for its emphasis on mixed-race identity as a desirable future for Indonesia. The campaign circulated primarily on Instagram through the account @polaasuh_, featuring a video in which an Indonesian woman narrates her experience of marrying a foreign national, migrating to her husband’s country, and raising a family abroad (@polaasuh_, 2024). The virality of this video underscores how mixed-race marriages are not merely private relationships but also public sites of discourse that invite both fascination and criticism. While some responses frame such marriages as aspirational and cosmopolitan, they are equally shaped by racialized perceptions and gendered ideologies that construct particular imaginaries of desirability, mobility, and modernity. These dynamics highlight the need to critically examine how marriage migration is represented, negotiated, and contested in digital spaces.

This study investigates the intersections of gender, race, and marital relationships by exploring social media narratives of Indonesian women married to foreign nationals. Using Instagram as the primary site of analysis, the research draws on social media posts as case studies to examine how racialized and gendered ideologies shape public perceptions of marriage migration. Through this lens, the study aims to illuminate the broader cultural and ideological frameworks that govern how transnational marriages are understood in contemporary Indonesia. To analyze these posts, the study employs Feminist Critical Discourse Analysis (FCDA), which incorporates various semiotic modalities—including visual images, spatial arrangements, gestures, and sound—to provide a comprehensive analysis of how power operates beyond just written or spoken text (Lazar, 2007; Hoeber, Shaw, and Rowe, 2024). This article begins with a focused literature review examining how marriage is represented in Indonesian academic discourse and national policy. This review highlights how narratives of gender, race, and migration intersect with political and legal structures in constructing ideologies about desirability and marital norms. In line with feminist critical discourse analysis, the literature review is not merely descriptive but also functions as a political act—challenging dominant frameworks and offering corrective interpretations through engagement with existing scholarship (Lazar, 2007). Building on this foundation, the article then analyzes Instagram posts that reflect the racialized narrative of bule (white individuals) as objects of desire. Finally, it examines posts that illustrate the politics of representation in mixed-race marriages and migration.

Continue Reading

Literature Review

Constructing the Ideal Partner: Gendered and Racialized Perceptions in Indonesia

The idea of desire, as articulated by Foucault (2014), plays a vital and dominant role in the discourse of sexuality and in shaping self-understanding. Foucault argues that desire is not a pre-existing or natural drive, but rather a product of power relations and social discourses—particularly those concerning sexuality. The discourse of desirability is shaped by the personal preferences of the community itself. In the Indonesian context, a desirable partner may be defined through various aspects, including culture, societal environment, sexual scripts, fetishization, and more. For instance, in cultural discourse, two of the dominant ethnic groups in Indonesia—the Javanese and the Sundanese—hold different norms in defining the ideal partner. For Javanese people, the idea of ideal partner is often articulated through the traditional concept of bibit, bobot, bebet—referring to the typology of marital quality—bibit refers to ‘lineage’, bobot refers to character or personality, and bebet refers to socioeconomic status or appearance (Khoiruddin, et. al., 2022). According to this typology, an individual who fulfills these three considerations is regarded as an ‘ideal partner’ in accordance with Javanese tradition and eligible for marriage.

In Sundanese culture—the second largest ethnic group in Indonesia—the conceptualization of the ‘ideal partner’ is traditionally grounded in the Sundanese philosophy of silih asah, silih asih, and silih asuh (Madjid, Abdulkarim, and Iqbal, 2016). These values, which emphasize mutual learning (asah), mutual love (asih), and mutual nurturing (asuh), are related to broader idealized Sundanese cultural traits of humility and kindness. Sundanese people are widely recognized for their gentle demeanor and respectful social conduct, and the philosophy of silih asah, silih asih, silih asuh is seen as a reflection of these characteristics (Madjid, Abdulkarim, and Iqbal, 2016). Conversely, in contemporary society, the construction of the ideal partner is informed by individual preferences, which are themselves shaped by broader socio-cultural influences. As reflected in contemporary social media discourse—particularly on Instagram—the conception of a desirable partner is frequently articulated in various contexts. For instance, in a recent podcast uploaded by Suara Berkelas (The High Voices), a young woman participant explicitly framed her preference for an ideal partner (man) in terms of survival ability, indicating that her ideal partner would be someone who has lived abroad, thereby enhancing their basic survival skills (Suara Berkelas, 2025). On the other hand, the Instagram account of Indonesian woman @addinashafira notably expresses a preference for foreign men, with posts having stated that she feels greater compatibility with them due to their open-mindedness, higher levels of acceptance, and the value they place on individuality—qualities that, in her view, reduce familial interference in the relationship. Both women are Indonesian, yet they hold differing preferences regarding the type of ideal partner for marriage.

As illustrated in the discussion above, the concept of an ideal partner is shaped by diverse narratives of sexual scripts. Simon and Gagnon (1973) argue that sexual scripts guide behavioral acts, which can be understood as manifestations of social constructions. The statements of the two Indonesian women above reflect sexual scripts embedded within the broader socio-cultural context of Indonesia. These scripts are influenced by individuals’ unique characteristics, preferences, and desires (Simon and Gagnon, 1986; 2003; Gagnon, 1990). Beyond cultural narratives of the ideal partner, individuals also maintain personal preferences in envisioning the person they hope to marry. However, in Indonesian society, the concept of ‘ideal partner’ is embedded within broader heteronormative expectations around the emotional, psychological, and physical attraction that drive human behavior (Seribu Tujuan, 2025). The ideology of heteronormative expectations in Indonesia is reinforced through gendered norms that promote motherhood as women’s primary role, while also institutionalizing the belief that women are chiefly responsible for their children’s well-being, as well as their family’s health, care, and education (Parker, 1993, cited in Blackwood, 2007).

This ideology of heteronormativity was largely introduced through colonialism and was particularly reinforced through Indonesian state regulations during former president Suharto’s regime. Colonial patterns of heteronormativity in Indonesia have roots in the Dutch East Indies period, when Dutch coloniser men engaged in intimate relationships with local Indonesian women in the seventeenth century (Stoler, 1995). Such relationships occurred either through legal marriage or informally with so-called nyai—women who served as housekeepers or concubines. During the Suharto era, this model of gender roles was subtly yet firmly developed as part of a broader strategy to ensure national stability (Blackwood, 2007). Conceptions of ideal masculinity and femininity were disseminated through state-sponsored initiatives, religious teachings, and pronouncements by Islamic leaders (Blackwood, 2007). In the post-colonial Indonesian state, these gender constructions reinforced a perceived ‘natural’ binary system, positioning women in domestic and supportive roles while assigning men authority in both family life and public spheres (Sears, 1996; Suryakusuma, cited 1996 in Blackwood, 2007). Suharto-era regulations directly reinforced heteronormativity as a central organizing principle (Ingraham, 1999). Consequently, heteronormativity in Indonesia became embedded in social structures and cultural discourse, shaping individual roles and perpetuating the state-sanctioned ideal of women as primarily mothers and wives (Blackwood, 2007).

Constructing Marriage: State Laws, Religion And Gendered Morality In Indonesia

Marriage in Indonesia is governed by Marriage Laws No. 1 of 1974, primarily regulating marriage under Indonesian legal provisions, covering the foundations of marriage, conditions, and restrictions, the legal age and consent for marriage, polygamy, and guardianship, divorce and annulment, prenuptial agreements and property, parenthood, and child status, and finally, interfaith marriage and legal disputes (Indonesian Marriage Law, 1974). These marriage laws consist of 67 articles organized into 11 chapters that serve as the fundamental legal basis for marriage in Indonesia. According to this law, the right to marry in Indonesia is grounded in four key aspects: (1) a marriage is lawful if it is conducted according to the laws of each party’s religion and belief; (2) each marriage must be registered in accordance with the prevailing legislation; (3) in principle, a man may only have one wife, and a woman may only have one husband; (4) the court may grant permission for a husband to have more than one wife if agreed upon by the parties involved (Indonesian Marriage Law, 1974).

Marriage regulation in Indonesia, as codified in the 1974 Marriage Law, prohibits interfaith unions, highlighting the central role of religion in state-sanctioned marital frameworks. A marriage is only considered valid and legal if it is solemnized between individuals of the same religion (Indonesian Marriage Law, 1974). Islam is the dominant religion, adhered to by approximately 87.2% of the population—equivalent to around 207.2 million people (Kardavi, 2002, cited in Robaj, 2021). Sharia law particularly influenced Indonesia’s Marriage Law No. 1 of 1974, which adopts the concept of marriage as a civil contract rather than a sacrament. In Islamic jurisprudence, marriage is the only religiously sanctioned means of engaging in legitimate sexual relations and procreation—especially following the abolition of practices such as slave concubinage—thus framing it as a mutual agreement between two individuals or their legal representatives (Brandeis University, n.d.). This contractual understanding is echoed in Chapter V of the Marriage Law, which allows for prenuptial agreements made in writing with mutual consent, either before or at the time of the marriage. Once registered, these agreements become legally binding, including for third parties. The contract must adhere to prevailing legal, religious, and moral norms, and any modifications during the marriage require mutual agreement and must not harm third-party interests (Indonesian Marriage Law, 1974).

Since the Dutch colonial period and prior to the implementation of the new Marriage Law, a diversity of marriage laws had been in force in Indonesia (Soewondo, 1977). The Dutch colonial administration played a significant role in shaping the legal regulation of marriage by institutionalizing a racially and religiously segregated legal system. Under Dutch rule, the Indonesian population was divided into three main groups: Europeans; Chinese, Arabs and Non-Chinese (Pradikta, Budianto, and Asnawi, 2024). This classification reflected the racialized social hierarchy of the colonial system and had direct implications for the application of marriage laws within the Dutch legal framework. Consequently, marriage recognition and regulation were deeply embedded in racial and ethnic categories (Khiyaroh, 2020). Prior to Dutch colonization, Islamic law governed marriage, but under colonial rule, it was marginalized and its influence significantly reduced (Pradikta, Budianto, and Asnawi, 2024). As a result, marriage laws were predominantly framed through Christian legal principles, resulting in mounting social tensions, particularly among the Muslim majority which comprised approximately 85% of the population. Therefore, most Indonesians remained subject to a combination of unwritten customary (adat) law and Islamic religious principles (Soewondo, 1977; Khiyaroh, 2020).

Sexual script theory, as developed by Simon and Gagnon (2003), provides a useful lens to analyze how Indonesian laws and religious norms co-produce normative gender and sexual behaviors. These scripts enforce heterosexuality as the only legitimate form of sexual expression—particularly through the institution of marriage (Murray, 2018). Sexual scripts in Indonesia are reflected in state laws, which define marriage as a union between a man and a woman and regulate the respective roles of husband and wife (Indonesia Marriage Law, 1974). This framework legitimizes sexuality strictly within heterosexual boundaries. The reinforcement of heterosexuality in the context of marriage in Indonesia is tied to the notion of the family as a vehicle for maintaining nationalist values and citizenry (Widianti, 2022). Thus, any form of marriage outside heterosexual norms is considered a criminal act under Indonesian law. Sexual scripts outside heterosexuality are prohibited under Article 45 of the Indonesian Criminal Code (KUHP), which states that consensual or non-consensual same-sex intercourse between adults over the age of 18 may be subject to criminal penalties (Widianti, 2022).

Indonesian law also regulates marriage across national and racial lines. Article 2 of the 1974 Marriage Law requires that marriages adhere to the religious laws of both parties, effectively restricting interfaith unions, which often intersect with mixed-nationality or mixed-race marriages. Moreover, administrative procedures for registering marriages involving foreign spouses add layers of legal scrutiny, including verification of nationality, residency, and consent from relevant authorities (Indonesian Marriage Law, 1974). Under Indonesian law, mixed-race or mixed-nationality marriages are permitted provided they comply with both state and religious regulations, and are performed within a heteronormative framework, allowing only unions between a man and a woman (Indonesian Marriage Law, 1974).

Implications for the Current Study

In conclusion, the concept of the ‘ideal partner’ in Indonesia is constructed through an interplay of sexual scripts, cultural narratives, individual preferences, and socio-polictical and historical structures. Sexual scripts mediate behaviors and desires within broader social and cultural frameworks, while local traditions—such as Javanese bibit, bobot, bebet and Sundanese silih asah, silih asih, silih asuh—demonstrate how ethnic and cultural values shape perceptions of marital suitability. Contemporary expressions of desirability, influenced by social media, coexist with these cultural norms, reflecting personal preferences and social aspirations. However, all these constructions are embedded within heteronormative expectations reinforced historically through colonialism, state policies, and gendered socio-religious norms, which continue to position women in domestic and supportive roles and men as authoritative figures.

Marriage governance in Indonesia thus reflects a system of gendered morality shaped by state law, Islamic doctrine, and colonial legacies. Legal and religious frameworks regulate marital contracts, divorce, and polygamy, reinforcing heteronormative gender roles that position husbands as authoritative providers and wives as domestic caregivers. By codifying these roles and enforcing sexual scripts, the state and religious authorities define legitimate sexuality and marginalize those outside heteronormative norms. This dual governance not only mirrors societal expectations but actively produces and sustains them, shaping citizenship, social belonging, and gendered inequalities. As this review of relevant scholarship and policy demonstrates, notions of desirability and the ideal partner are not merely personal or cultural constructs but are deeply embedded in power relations, social discourse, political and legal frameworks, and historical legacies within Indonesian society.

Bule as Racialized Desire

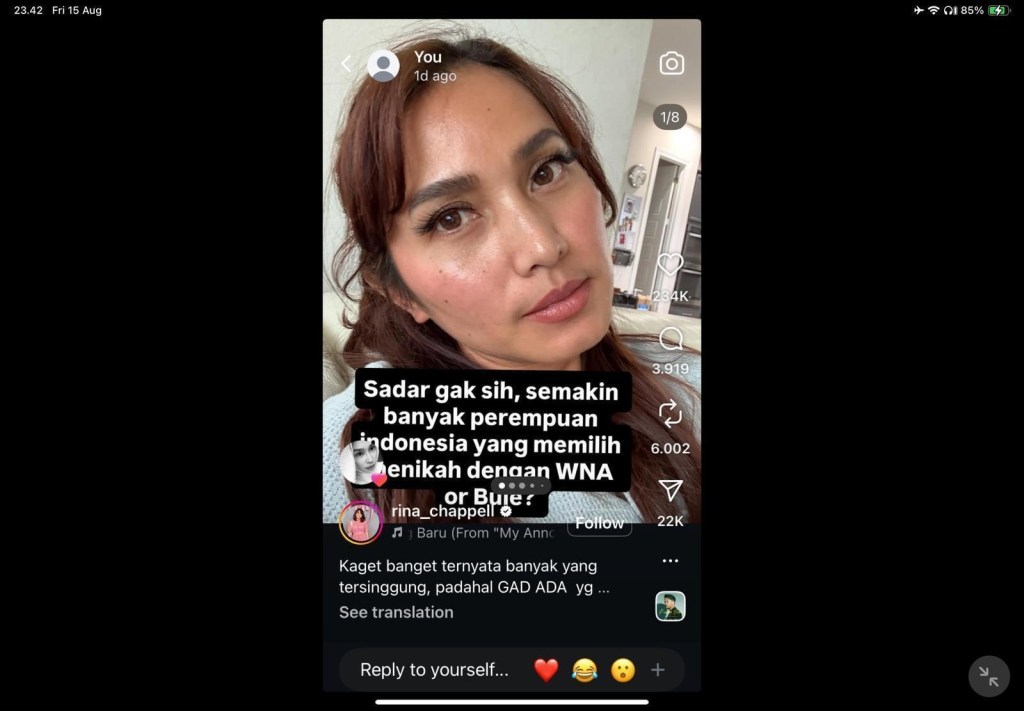

The discourse on partner desirability in Indonesia has been explored through multiple analytical lenses, particularly in relation to gender and race. As demonstrated in the preceding discussion, individuals’ preferences are not merely personal choices but are shaped by broader socio-cultural, historical, and normative frameworks. Within this context, racialized narratives intersect with gendered expectations, influencing how certain groups are perceived as desirable partners. In Indonesia, the term ‘white’, commonly referred to as bule, is not solely understood as a racial category but also signifies a social hierarchy. According to Fechter (2003), the term bule is deliberately used to address white foreigners, primarily based on their skin pigmentation. Consequently, on social media platforms—particularly Instagram—the term bule is widely used to refer to white foreigners. As illustrated by @rina_chappell in a 2025 Instagram post (Figure 1), this usage reflects the consciousness of Indonesian women who choose white partners (Chappell, 2025):

Figure 1: @rina_chappell Instagram post (Chappell, 2025)

The post features text reading, ‘do you realize that more and more Indonesian women are preferably choosing to marry foreigners or Western men?’ (Chappell, 2025, my translation). This discussion of bule on @rina_chappell’s account frames foreigners, particularly white individuals, as superior and ideal partners compared to Indonesian partners. This narrative is supported by a 2015 study conducted in Yogyakarta, Indonesia, which highlights Indonesian women’s perceptions of bule and suggests that white individuals are considered wealthy and more capable of fulfilling their needs compared to Indonesian men (Perdana and Nuryanti, 2015). Despite this appeal, the perception of bule is also influenced by physical appearance. Perdana and Nuryanti (2015) further note that Indonesian women’s interest in marrying foreigners, particularly white individuals, is often linked to the perception that such unions can enhance their familial lineage as well as improve their social status. This desired improvement of familial lineage and social status is reflected in a recent Instagram post by @spicy_and.sour (Figure 2):

Figure 2: @spicy_and.sour Instagram reel video (spicy_and.sour, 2025)

The post features a video with the words, ‘dear Future Kids, your dad is western man. You will have three citizenships. You’re welcome’ (spicy_and.sour, 2025, my translation). This reference to the user’s future children’s expected gratitude at their mother’s choice of bule partner reflects the perceived improvement of familial lineage and social status, suggesting that white individuals are socially constructed as superior or more desirable partners. This portrayal on social media demonstrates how perceptions of bule are shaped by racialized ideologies that glorify whiteness and reinforce hierarchies of desirability.

In summary, the discourse on partner desirability in Indonesia is deeply intertwined with both gendered and racialized frameworks. The term bule illustrates how whiteness is socially constructed as a marker of superiority and desirability, extending beyond mere racial classification to signify social hierarchy, wealth, and elevated status. Social media platforms, such as Instagram, play a significant role in circulating and reinforcing these perceptions, framing white individuals as ideal partners in contrast to local Indonesian men. This phenomenon highlights the intersection of racialized ideologies and gendered expectations, revealing how broader socio-cultural and historical narratives continue to shape intimate preferences, partner selection, and perceptions of marital value in contemporary Indonesian society.

The Politics of Representation in Mixed-Race Marriage Migration

Analysis of sexual scripts surrounding mixed-race marriages in Indonesia reveals several recurring patterns. Typically, the husband is depicted as a foreigner, often with white skin, while the wife is portrayed as a local Indonesian woman. The couple either marries and settles in the husband’s country or relocates to Indonesia. Additionally, the wife frequently assumes the role of a content creator, sharing her experiences and offering guidance to Indonesian women interested in pursuing relationships or marriage with foreign partners (based on content from Instagram accounts such as @rina_chappell and @spicy_and.sour). For example, @sabirov.family is an Instagram account managed by a mixed-race couple consisting of an Indonesian woman of Javanese descent and a Russian man. The couple has a son and currently resides in Bali, Indonesia, following the husband’s relocation from Russia (sabirov.family, 2025). The @sabirov.family account currently has 88.8K followers, reflecting significant public interest in their lives as a mixed-race couple. The account gained popularity due to their content showcasing cultural exchange, and most of their posts primarily focus on family life, daily activities, experiences of mixed-race living, travel, and related topics. In examining sexual scripts and marriage migration, this account illustrates a heteronormative image of family, alongside the husband’s adaptation to migration from Russia to Bali. Furthermore, the account reflects racialized ideologies that valorize white individuals, as demonstrated in Figure 3 below:

Figure 3. @sabirov.family Instagram reel video (sabirov.family, 2024)

In this video, a wife (whose name is not explicitly mentioned) performs a dance with her husband appearing in the background, accompanied by the caption: ‘POV (Point of View): although marrying a white person (bule), I am still a Javanese woman’ (sabirov.family, 2024, my translation). The phrasing of ‘although’ can be read to imply a perceived elevation in status associated with marrying a white partner, highlighting the interplay between racialized desirability and social hierarchy. As sociolinguistics posit, language is not only a tool for communication but also reflects and shapes identity, status, and social roles (Mujib, 2009; Ibrahim, 2025). From a feminist intersectional perspective, identity, status, and social roles are intertwined and mutually constitutive, shaped and reinforced through language (Crenshaw, 1989). Thus, this Instagram reel illustrates how race, gender roles, identity, and marital dynamics intersect to influence social mobility, drawing widespread public attention with 436K likes. The high engagement suggests that Indonesian society continues to perceive whiteness in mixed-race marriages as particularly desirable and socially intriguing, reflecting broader cultural attitudes toward racialized desirability.

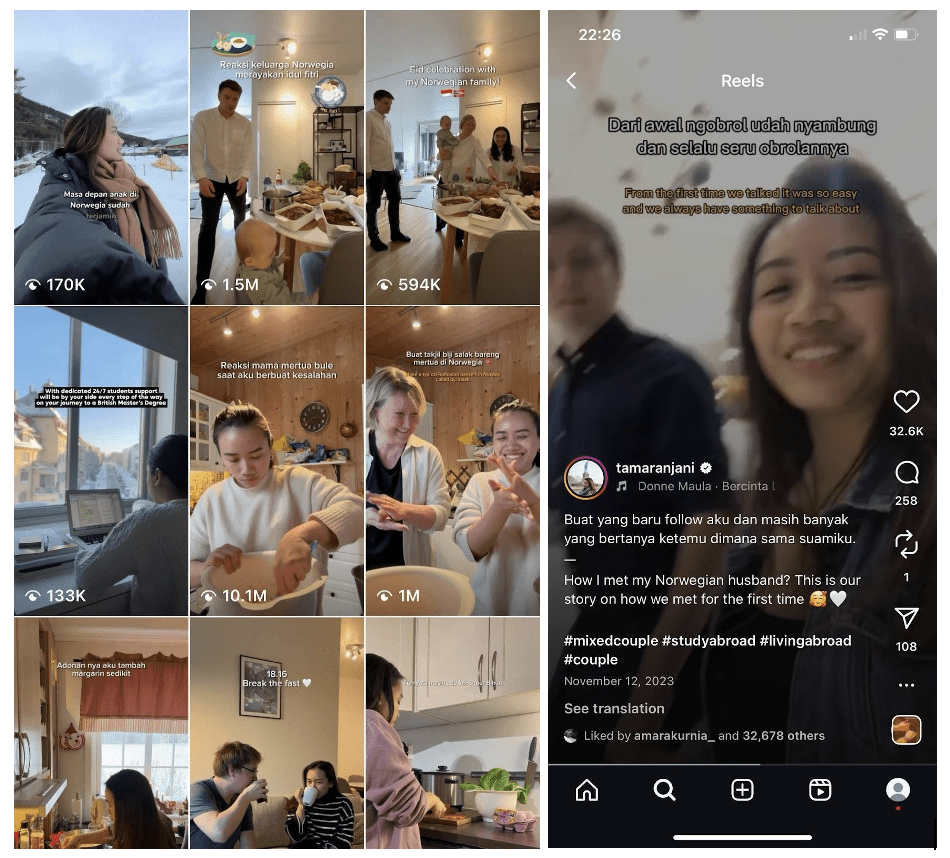

The Instagram handle @tamaranjani also attracts public interest in mixed-race families. This account is owned by an Indonesian woman named Tamara Anjani, who currently resides in Norway with her Norwegian husband. Her content gained significant attention on Instagram when she was studying in Singapore, meeting her husband during that time. Tamara has amassed a substantial following, reaching 307K followers on Instagram (Anjani, 2025). Similarly to @sabirov.family, this account serves as an explicit representation of heteronormative family structures while simultaneously perpetuating racialized ideologies, framing marriage to white partners and international migration as socially desirable trajectories. However, there is a notable distinction between the accounts @sabirov.family and @tamaranjani. While the Sabirov family portrays the husband relocating to Indonesia, Tamara Anjani documents her own move to Europe—specifically Norway—to live with her husband (Anjani, 2025).

Figure 4: @tamaranjani Instagram reels page (Anjani, 2025)

Figure 5: @tamaranjani post (Anjani, 2023)

Analyzing Figures 4 and 5 through a mixed-race marriage migration framework, this social media account can be viewed as representing the discourse of European people’s marital relationship with ‘natives’/immigrants, demonstrating multicultural identity in marriage (Hendrickx, Lammers, and Ultee, 1991; O’Leary and Finnas, 2002; Kalmijn and van Tubergen, 2006 cited in Gonzalez-Ferrer et al., 2018). The posts illustrate the dynamics of mixed-race marriage and migration, as Tamara documents her experiences of cultural exchange after moving abroad: building a close relationship with her mother-in-law, cooking Indonesian dishes in Norway, sharing her daily life with her husband, celebrating Eid with her Norwegian family, and engaging in language acquisition (Anjani, 2023; 2025). Her portrayal of everyday life in Norway generates public interest, particularly as mixed-race marriage is often perceived by Indonesian women as a desirable pathway. As noted by Perdana and Nuryanti (2025), mixed-race marriage and relocation to the husband’s country are frequently associated with the prospect of attaining a better quality of life. Therefore, the @tamaraanjani account exemplifies how mixed-race marriage and marriage migration are constructed as pathways to improving various aspects of life from the perspective of Indonesian women. These include: (1) achieving a better quality of life, (2) engaging in cultural exchange, and (3) enhancing familial lineage. Such representations not only reinforce the desirability of transnational unions but also reflect underlying gendered and racialized ideologies in which whiteness, mobility, and foreignness are positioned as markers of prestige, opportunity, and upward social mobility.

Marriage Migration and Progressive Whiteness

Andita Hasna, known on Instagram as @anditahsn, is an Indonesian woman who married a German man in 2021. She is originally from Semarang, Indonesia. Prior to marrying her German husband, she was a student at Swiss German University and Fachhochschule Südwestfalen, where she pursued a double bachelor’s degree in Economics and Business Informatics, as well as a master’s degree in International Management and Information Systems (Hasna Paramitha, 2025). During her study abroad journey, Andita often posted her experiences on Instagram. After marrying her husband, she has frequently shared content about her daily life as a wife to a German partner, her pregnancy journey, and, more recently, numerous posts about her toddler (Hasna Paramitha, 2025).

One of Andita’s Instagram videos (Figure 6) engages with public perceptions of marrying foreigners, particularly white men, who are often constructed as less patriarchal compared to Indonesian men. This perception aligns with previous research on marriage migration and interracial relationships, which highlights how foreign men—especially white men—are frequently idealized as more egalitarian, attentive, and supportive partners compared to local men (Constable, 2005; Nemoto, 2006). Such narratives illustrate how interracial unions are framed within gendered hierarchies and racialized ideologies of desirability.

Figure 6: @anditahsn Instagram video reel (Hasna Paramitha, 2024)

In the video’s caption, Andita explicitly states: ‘The attractiveness of a man lies not only in his appearance, but also in his rejection of patriarchal attitudes and his role as a family man’ (Hasna Paramitha, 2024, my translation). This articulation positions her husband as embodying qualities that challenge patriarchal norms, thereby reinforcing public perceptions of white partners as more open-minded, egalitarian, and attentive compared to Indonesian men. Such representations resonate with broader racialized ideologies that construct whiteness as a marker of modernity and progressive gender relations (Parreñas & Kim, 2011). Furthermore, by highlighting the non-patriarchal attributes of her spouse, Andita’s narrative exemplifies how social media content contributes to shaping and legitimizing cultural imaginaries of desirability in mixed-race marriages (Hasna Paramitha, 2024). In summary, the framing of mixed-race marriage by @anditahsn not only reflects personal experiences but also inadvertently reinforces gendered and racialized narratives of whiteness that are prevalent in Indonesian society. Her content, which emphasizes the perceived openness and non-patriarchal nature of her foreign partner, contributes to the normalization of public perceptions that white individuals are more desirable partners. Given the popularity of her account, these portrayals have a significant reach, shaping social attitudes and reinforcing existing hierarchies of desirability based on race and gender. Consequently, social media functions as a powerful platform through which sexual scripts, cultural ideals, and racialized ideologies are circulated and reproduced, influencing both individual aspirations and broader societal perceptions of mixed-race marriage. This underscores the intersection of digital media, gender norms, and racial hierarchies in constructing contemporary understandings of partner desirability in Indonesia.

Conclusion

In the Indonesian context, the notion of a desirable partner is shaped by cultural discourses and contemporary societal values, resulting in specific preferences in defining the ‘ideal partner’. Gender relations within this framework are mediated through sexual scripts and heteronormative expectations, reflecting the country’s emphasis on familial lineage and the centrality of heterosexual partnerships. Heteronormativity thus underpins both the selection of a partner and the social legitimacy of romantic relationships. Beyond these gendered norms, the concept of the ideal partner is also influenced by racialized desires and socially constructed notions of race, which contribute to the privileging of white partners within public perception. Social norms and social media play a significant role in circulating and reinforcing these preferences, shaping cultural imaginaries of desirability and establishing racial hierarchies that intersect with gendered expectations in contemporary Indonesian society.

Indonesian marital laws reflect multiple historical, social, and religious influences, including: (1) the legacy of the Dutch colonial system, which contributed to racial segregation and hierarchical social structures; (2) post-colonial dynamics that reinforced heteronormativity in shaping family structures and constructing women primarily as reproductive subjects; (3) the influence of Islamic norms and interpretations in regulating marital aspects, including sex, religion, and related obligations; (4) the framing of gendered morality through a heteronormative lens, which positions marriage not only as a sexual institution but also as a regulatory mechanism governing social conduct; and (5) state regulations that further shape and institutionalize gendered expectations of marriage. Collectively, these factors illustrate how Indonesian marital laws operate at the intersection of colonial history, religion, gender norms, and state governance, producing a complex framework that both reflects and enforces societal hierarchies.

Finally, gendered and racialized perceptions of mixed-race marriage are constructed and disseminated through social media platforms, exemplified by accounts such as @rina_chappell, @spicy_and.sour, @sabirov.family, @tamaranjani, and @anditahsn, which document the lived experiences of couples engaged in mixed-race unions and marriage migration. These representations underscore several salient themes: (1) the articulation of gendered and racialized desire within heteronormative family frameworks; (2) the depiction of mixed-race marriage as a mechanism for social mobility and the enhancement of social status; (3) the narrative that unions with foreign partners contribute to the improvement of individual life trajectories and the elevation of familial lineage; and (4) the instrumental role of social media in constructing, reproducing, and amplifying these narratives, thereby influencing public perceptions and generating engagement with the phenomenon of mixed-race marriage. Such portrayals reflect broader socio-cultural discourses on race, gender, and desirability, illustrating how digital media functions as a critical arena in which societal norms and hierarchies are negotiated, reinforced, and contested.

Acknowledgements

I sincerely thank my master’s supervisor, Ernesto Vasquez del Aguila, for his invaluable guidance and numerous insights throughout this research. I am also deeply grateful to the University College Dublin, School of Social Work, Social Justice and Social Policy, for providing an intellectually rich and supportive academic environment.

I extend my heartfelt appreciation to my family and to myself for the continuous encouragement, strength, and perseverance that made this work possible.

This research was funded by the LPDP Scholarship from the Ministry of Finance, Republic of Indonesia.

ORCID iD

Nissa Vidyanita ![]() https://orcid.org/0009-0003-0888-0196

https://orcid.org/0009-0003-0888-0196

Funding

This work was supported by the LPDP Scholarship by the Ministry of Fund.

Declaration of Competing Interests

The author declares that the funding body had no role in the study design; data collection, analysis, interpretation, or manuscript preparation, and that there are no competing interests.

Statement on AI Use

The author declares that the artificial intelligence (AI) tool ChatGpt was used to assist in manuscript preparation. AI was used solely for language editing purposes, translation, and formatting, and all content, interpretation and conclusions are the author’s own.

References

Anjani, T. N. (2025) Instagram profile. Available at: https://www.instagram.com/tamaranjani/.

Anjani, T. N. (2023) ‘How I met my Norwegian husband? This is our story…’, [Instagram]. 12 November. Available at: https://www.instagram.com/reel/CzjHwc9tWS5/?igsh=MTA0cXJ2Mmh3NmE2aA==.

Bergunder, M. (2014) ‘What is religion?’ Method & Theory in the Study of Religion, 26(3), pp. 246-286. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1163/15700682-12341320.

Blackwood, E. (2007) ‘Regulation of sexuality in Indonesian discourse: Normative gender, criminal law and shifting strategies of control’, Culture, Health & Sexuality, 9(3), pp. 293-307. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13691050601120589.

Bratter, J. L., and Eschbach, K. (2006) ‘“What about the couple?” Interracial marriage and psychological distress’, Social Science Research, 35(4), pp. 1025-1047. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2005.09.001.

Buggs, S. G. (2017) ‘Dating in the time of #BlackLivesMatter: Exploring mixed-race women’s discourses of race and racism’, Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, 3(4), pp. 538-551. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/2332649217702658.

Chappell, H. A. (2025) ‘Banyak Perempuan Baik’, [Instagram]. 6 August. Available at: https://www.instagram.com/p/DM_w0VHuB72/?img_index=1.

Charsley, K., Bolognani, M., and Spencer, S. (2017) ‘Marriage migration and integration’, Ethnicities, 17(4), pp. 469-490. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/26413966.

Constable, N. (2005) Cross-border marriages: Gender and mobility in transnational Asia. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Courtice, E. L., and Shaughnessy, K. (2018) ‘The partner context of sexual minority women’s and men’s cybersex experiences: Implications for the traditional sexual script’, Sex Roles, 78(3–4), pp. 272-285. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-017-0792-5.

Crenshaw, K. (1989) ‘Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics’, University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989(1), pp. 139-167. Available at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1989/iss1/8.

Dugard, J., and Sanchez, M. A. (2021) ‘Bringing gender and class into the frame: An intersectional analysis of the decoloniality-as-race critique of the use of law for social change’, Stellenbosch Law Review, 32(1), pp. 24–42. Available at: https://doi.org/10.47348/SLR/v32/i1a2.

Febriani, G. A. (2022) ‘Kisah wanita viral dinikahi bule Norwegia ganteng, bikin warganet baper’, Wolipop, September 7. Available at: https://wolipop.detik.com/wedding-news/d-6276149/kisah-wanita-viral-dinikahi-bule-norwegia-ganteng-bikin-warganet-baper.

Fechter, A-M. (2003) ‘Don’t call me bule!: How expatriates experience a word’, Living in Indonesia, July. Available at: https://www.expat.or.id/info/dontcallmebule.html.

Foucault, M. (2014) The history of sexuality, volume 1: An introduction. Translated by R. Hurley. New York: Vintage International.

Gonzalez-Ferrer, A. et al. (2018) ‘Mixed marriages between immigrants and natives in Spain: The gendered effect of marriage market constraints’, Demographic Research, 39, pp. 1+. Available at: https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A572943506/AONE?u=anon~dd1f749b&sid=googleScholar&xid=4d6c60e7.

Groes, C., and Fernández, N. T. (eds.) (2018) Intimate mobilities: Sexual economies, marriage and migration in a disparate world. New York: Berghahn Books.

Hasna Paramitha, A. (2024) ‘Ternyata makin tua, makin-makin pesonanya’, [Instagram]. 18 June. Available at:https://www.instagram.com/reel/C8XDP2PBuuw/?igsh=ZjI3YW5jc25lcTIz.

Hasna Paramitha, A. (2025) Instagram profile. Available at:https://www.instagram.com/anditahsn/.

Hendrickx, J., Lammers, J. & Ultee, W.C., 1991. Religious assortative marriage in the Netherlands, 1938–1983. Review of Religious Research, 33(2), pp.123–145.

Hoeber, L., Shaw, S., and Rowe, K. (2024) ‘Advancing women’s cycling through digital activism: A feminist critical discourse analysis’, European Sport Management Quarterly, 24(5), pp. 1111-1130. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2023.2257727.

Hoogenraad, H. (2023) ‘A case of cruel optimism: White Australian women’s experiences of marriage migration’, Gender, Place & Culture, 30(9), pp. 1199-1219. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2022.2049218.

Ibrahim, M. (2025) ‘Bahasa dan kelas sosial: Hubungan antara pilihan kata dan status sosial’, Proceedings Series on Health & Medical Sciences, 7, Proceedings of the 1st National Seminar on Global Health and Social Issue (LAGHOSI). Available at: https://doi.org/10.30595/pshms.v7i.1456.

Khoiruddin, D., Syamsuddin, S., and Baehaqi, B. 2024, ‘Tinjauan hukum Islam terhadap metode bibit bebet bobot dalam memilih pasangan suami istri’, Al Hukmu: Journal of Islamic Law and Economics, 3(1) pp. 6-13. Available at: https://doi.org/10.54090/hukmu.305.

Khiyaroh. (2020) Alasan dan tujuan lahirnya Undang-Undang Nomor 1 Tahun 1974 tentang perkawinan. Al-Qadha: Jurnal Hukum Islam dan Perundang-Undangan, 7(1), 1-15. Available at: https://doi.org/10.32505/qadha.v7i1.1817.

Lazar, M. M. (2007) Feminist critical discourse analysis: Gender, power, and ideology in discourse. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Madjid, M.A.S.R.V., Abdulkarim, A., and Iqbal, M. 2016, ‘Peran nilai budaya Sunda dalam pola asuh orang tua bagi pembentukan karakter sosial anak’, International Journal Pedagogy of Social Studies, 1(1), pp. 1-7. Available at: https://doi.org/10.17509/ijposs.v1i1.4956.

Mujib, A., 2009. Hubungan bahasa dan kebudayaan (perspektif sosiolinguistik). Adabiyyāt: Jurnal Bahasa dan Sastra, 8(1), pp. 141–154. Available at: https://doi.org/10.14421/ajbs.2009.08107

Murray, S. H. (2018) ‘Heterosexual men’s sexual desire: Supported by, or deviating from, traditional masculinity norms and sexual scripts?’ Sex Roles, 78(2), pp. 1-12. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-017-0766-7.

Nemoto, K. (2006) ‘Intimacy, desire, and the construction of self in relationships between Asian American women and white American men’, Journal of Asian American Studies 9(1), pp. 27-54. Available at: https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/jaas.2006.0004.

Novita, E. (2021) ‘Identifikasi pembentukan identitas orientasi seksual pada homoseksual (gay)’, Jurnal Penelitian Pendidikan, Psikologi dan Kesehatan (J-P3K), 2(2), pp. 194-205. Available at: https://doi.org/10.51849/j-p3k.v2i2.99.

O’Leary, R. & Finnäs, F., 2002. Education, social integration and minority–majority group intermarriage. Sociology, 36(2), pp.235–254.

Palriwala, R., and Uberoi, P. (eds.) (2008) Marriage, migration and gender. Gurugram: SAGE Publications India.

Parreñas, R.S. & Kim, J., 2011. Multicultural East Asia: An Introduction. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, December 2011.

Perdana, M. P., and Nuryanti, L. (2015) ‘Faktor-faktor yang mempengaruhi minat perempuan Indonesia untuk menikah dengan pria warga negara asing: Studi kasus di Yogyakarta’, Journal Indigenous, 13(1), pp. 1-14.

Pradikta, H. Y., Budianto, A., and Asnawi, H. S. (2024) ‘History of development and reform of family law in Indonesia and Malaysia’, The First Annual International Conference on Social, Literacy, Art, History, Library, and Information Science (ICOLIS 2024). Islamic State University of Raden Intan Lampung, 9-11 October 2023. Dubai: KnE Social Sciences, pp. 316-331.

Prianti, D. D. (2019) ‘The identity politics of masculinity as a colonial legacy’, Journal of Intercultural Studies, 40(6), pp. 700-719. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/07256868.2019.1675612.

Robaj, A. (2021) ‘Marriage according to the Islamic law (Sharia) and the secular law’, Perspectives of Law and Public Administration, 10(2), 19-24.

Sabirov.family (2024) ‘Terus pada bilang “kok masih medok??”…’ [Instagram]. 17 June. Available at: https://www.instagram.com/reel/C8UMLt_JTw7/?igsh=eHMzMzVldGpzdTFx.

Sabirov.family (2025) Instagram profile. Available at: https://www.instagram.com/sabirov.family/.

Sears, L. J. (1996) Shadows of empire: Colonial discourse and Javanese tales. Durham: Duke University Press.

Seribu Tujuan (2025) ‘Stigma and discrimination: LGBTQ+’, Reprodukasi by Seribu Tujuan. Available at: https://www.seributujuan.id/reprodukasi-en/stigma-and-discrimination-lgbt.

Simon, W., and Gagnon, J. H. (1973) Sexual conduct: The social sources of human sexuality. Chicago: Aldine Publishing Company.

Simon, W., and Gagnon, J. H. (2003) ‘Sexual scripts: Origins, influences and changes’, Qualitative Sociology, 26, pp. 491-497. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1023/B:QUAS.0000005053.99846.e5.

Soewondo, N. (1977) ‘The Indonesian marriage law and its implementing regulation’, Archipel, 13, pp. 283-294. Available at: https://www.persee.fr/doc/arch_0044-8613_1977_num_13_1_1344.

Spicy_and.sour (2025) ‘Dear future kids…’ [Instagram]. 26 June. Available at: https://www.instagram.com/p/DLWx07To9hi/.

Stoler, A. L. (1995) Race and the education of desire: Foucault’s history of sexuality and the colonial order of things. Durham: Duke University Press.

Suara Berkelas (2025) Bedah Mindset Perempuan Berkelas, Suara Berkelas [Podcast]. 28 August 2025. Available at: https://podcasts.apple.com/id/podcast/suara-berkelas/id1775161378.

Undang-Undang Republik Indonesia Nomor 1 Tahun 1974 tentang Perkawinan [Indonesian Marriage Law] (1974) Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 1974.

Wieringa, S.E., 2015. Heteronormativity, Passionate Aesthetics and Symbolic Subversion in Asia. Sussex Academic Press.

Widianti, S. (2022) ‘Compulsory heterosexuality in Indonesia: A literary exploration of the work of Ayu Utami’, Religions, 13(10), 1002. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13101002.

©Vidyanita, Nissa 2025. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.